We are thrilled to have permission to bring you this article by Pamela Whitman Mattson, first published in the April/May 2011 issue of The Ocean Magazine. Thank you to Robert Wald and Pamela Whitman Mattson. As in the original article, all photographs are courtesy of the Whitman Family Collection.

EAST WEST – The William Francis Whitman Family

Introduction

In general, very little is known on the West Coast and beyond of the original East Coast surfing pioneers of yesteryear, including a most unusual family known as the Whitmans. The Ocean Magazine feels it is now time to pay due respect and honor this most unique family.

As will be revealed in the following article centered around the life of William Francis Whitman (1914 – 2007), you will learn of the remarkable influence that this incredibly sharp and highly driven, productive family has had on surfing and culture. Three generations of family members have been, and continue to be, players in professional careers and hobbies from surfing, horticulture, free skin diving, spearfishing, fiberglass boat manufacturing, cinematography, aeronautics, and a host of other activities. Read on.

William Francis Whitman was the first of three sons born to a Chicago industrialist who owned the second largest printing company in the city. Following William came the birth of his second eldest brother, Stanley, both of whom were born in northern states, and finally the arrival of his youngest sibling, Dudley, who was born in Miami. After spending several winters in the sub-tropical weather of Florida to escape the wrath of the Windy City, his father, in 1920, had decided to build his first permanent winter home in Miami. It was there they lived a privileged life, where adjacent to their home, William’s father built a servants’ quarters which housed a butler, maid and cook. This was the 1920s. Everything was so much more inexpensive, and oceanfront cottages in Miami were spaced about a half mile apart, with vacant land in between – a far cry from the high density, close living quarters of today’s civilization where people scratch and snarl over every centimeter of land . . . and penny.

Prior to a devastating hurricane in 1926, real estate prices soared in Miami, especially at the height of the Florida land boom. William’s father became involved in this speculative gamble and wound up owning blocks of oceanfront property near South Beach, Miami. After the 1926 hurricane came ashore and finally subsided, it had deposited four feet of wet beach sand in the Whitman’s ocean-facing dining room. A two-story structure just north of the Whitmans was gone without a trace. On calm ocean days, when the offshore water was clear, the red brick chimney could be seen a short distance out in the ocean, resting on the seabed. Fortunately for the Whitman family, they were out of town when this devastating hurricane hit full-force.

In 1929, the Great Depression hit. William’s father felt the impact of a slowed economy and decided to have William attend home schooling on Miami Beach. “It was exciting to be able to spend my first winter back in a snow-and-ice-free subtropical climate,” William said in an interview before his death. “The high school instructors proved to be outstanding and I graduated with the class of 1934.

“After attending the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor for two years, I entered the University of Florida at Gainesville, where I graduated in 1939, with a Bachelor of Science degree in Business Administration.” By the time William’s father passed away in 1936, he was a well-respected Miami Beach pioneer and developer. His wife, Leona Erickson Whitman, proved to be a shrewd businesswoman and greatly enhanced the Whitman’s family fortune. Together they built a ten-story, one-hundred and fifty-room hotel called “Whitman by the Sea.”

Love for the Ocean Leads In Many Directions

William and his youngest brother, Dudley, had always been marine-oriented. At an early age they learned to body surf and ride waves

proned out on belly surfboards. Then, during the winter of 1930, they observed for the first time three Virginia surfers actually stand up and ride a Hawaiian-type board on the incoming waves off Miami Beach. After borrowing their board for a few trials, William built a similar board of his own. This is believed to be the first surfboard ever constructed in Florida.

“Using a drawknife on a four-inch thick white pine plank,” William recalled, “I came up with an eighty-seven pound board. Dudley did the same thing using redwood. These were pioneer wave-riding days, and we believe we were the first Florida residents surfers to take up this aquatic sport.”

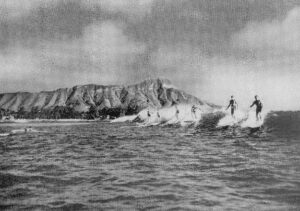

Classic 1940’s Waikiki, Hawaii postcard. William Whitman is the surfer third from right. Notice no high-rise hotels?

William and Dudley would soon meet world surfing legend Tom Blake and his advanced hollow wood surfboard designs of that era. Soon the Whitmans took to riding and building much lighter, hollow-built surfboards, which they introduced to Daytona Beach.

In a recent interview with Dudley (who in his 90s still resides in Florida), the following story is how his brother William and he had met Tom Blake:

“Tom Blake, John Smith and Babe Ridgeway were the first surfers onthe East Coast from Virginia Beach. They headed south to Florida surfing and heard about the surfing brothers from Miami Beach—Bill and Dudley Whitman. William had already finished his first surfboard made out of Sugar Pine that was 10 feet long, 24 inches wide and 10 inches thick. I was finishing the final touches on my first surfboard in the home workshop that our father had built in Miami Beach, located between 32nd and 33rd streets on Collins Avenue. I looked out the window and saw a guy named Tom Blake, paddling a hollow surfboard. Not long after, the three of us became the closest and best lifetime friends. “Blake was an orphan and met Duke Kahanamoku at a gathering in a Detroit theatre near where Blake grew up. By then, the Duke was a famous athlete and five-time Olympic Medalist in swimming and spreading the sport of surfing. After meeting The Duke, Blake immediately decided he wanted to become a world-class swimmer and surfer. Blake soon went to Hawaii and became life long friends with Duke Kahanamoku.”

After surfing for almost a year, it was during the summer of 1937 that William and Dudley put their homemade hollow surfboards atop their convertible and drove to California. On arrival in Los Angeles, they were joined by Tom Blake and spent their first week in California riding West Coast waves with Blake.

“After that first week in California,” William said, “we took our surfboards and boarded the Matson Steamship ‘Lurline’ bound for Honolulu, Hawaii.

The Whitman brothers then unpacked their surfboards from the canvas on the beach and a crowd of at least fifty Hawaiians crowded around the surfboards marveling at the craftsmanship and innovative hollow wood design. These surfboards were literally state-of-the-art and no one had seen such craftsmanship and beauty.”

One day, with nothing to do but “hang out,” William and his brother Dudley saw a native Hawaiian walk by on the wet sand. He was

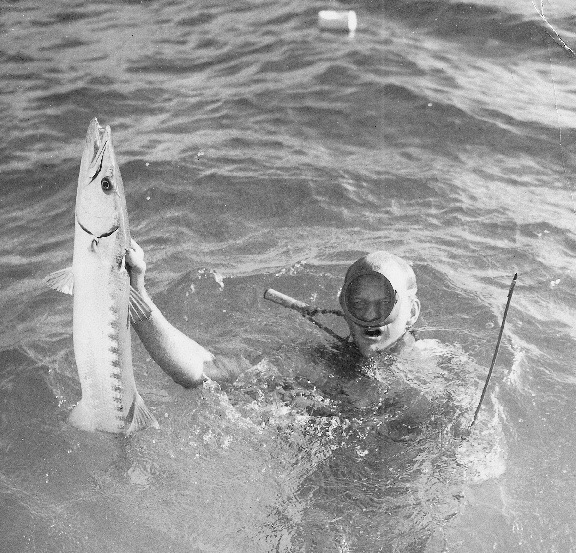

William Whitman proudly stands next to the largest fish he ever speared – a 375 lb Grouper. Jupiter Inlet, Florida

carrying goggles, a spear, a sling, and a long string of rainbow-colored reef fish. They immediately approached the local Hawaiian and asked how he acquired the fish. He replied that the fish were speared underwater and the same equipment he was using could be bought at a nearby local Japanese fishing supply store. It was there they purchased a complete outfit to spear marine life beneath the sea. “Our problem,” William remembered, “was that the carved wooden diving goggles gave us double vision. As two fish swam by, we observed four, and it was impossible to decide at which to aim our rubber propelled spear (known as a ‘Hawaiian Sling’).”

They soon learned that substituting the poorly fitting goggles with a glass face mask (originally developed by the Japanese), worked wonders. Gone was the double vision, and on their first spear fishing trip with their new face masks, they returned home in less than a half hour with a long string of speared fish. As their surfing safari came to an end, the Whitmans wondered if these same Hawaiian spearfishing techniques would work in Florida’s coastal waters. “It appeared no one back home had thought of spearing fish while submerged, Hawaiian-style,” William said. “Florida’s fish population in the 1930s was unbelievable. Viewed from inlet bridges, on the clear incoming tide, the bottom was obscured by thousands of snook swimming against the swiftly flowing current.” The outer coral reefs of the Florida Keys had a saltwater fish population unequalled anywhere else in the United States.

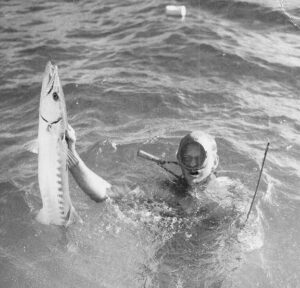

William holds up an Atlantic Barracuda, known for their razor sharp teeth and extreme speed underwater.

William and Dudley did most of their Florida skin diving and spear fishing off Key Largo on the outer reefs. Soon, others from Miami followed suit, and over a period of time, there developed a confrontation with charter fishing boat captains working out of this same boat launching area. The final result was that the commercial boat interests, with help from The Miami Herald, were able to have legislation passed establishing a coral reef state park, effectively putting an end to spear fishing in the Upper Keys.

Of his most memorable experiences skin diving, William remembers “the time I was bitten by a shark and later a moray eel, none of which were too serious injuries. What could have ended my skin diving for good occurred off Hobe Sound, Florida. Swimming a block offshore with a boat, I saw a huge school of ladyfish approaching. Entering this cloud of closely packed silvery fish had completely obscured my vision. Finally, when I did see the light of day, there was an eleven-foot shark trailing the passing school. The shark held its course, closing in on me, and I had only seconds to act. Now, with this predator only a few feet away, I used my spear to give it a warning nose jab, hoping to fend it away. What happened next I am unaware of, as the shark violently churned up the sandy bottom, obscuring everything in sight. When I could see again, the shark had disappeared. I have found it best to be aggressive with sharks, and fortunately this saved me. The largest fish I have successfully speared was a 375-pound grouper, big enough to clamp onto and drown a person. It was on the very same day I captured this huge grouper that the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.”

Wartime Service

With the U.S. at war on two fronts, it was a common sight to see Allied oil tankers aflame off Florida’s East Coast after being hit by a German sub. One year prior, William had enrolled in an aircraft metal working course, and with this new background, he qualified as a sheet metal template maker with an aircraft manufacturer.

“As World War II heated up,” William recalled, “I enrolled in the U.S. Coast Guard. It was our assignment to maintain navigational aids along the Intercoastal Waterway. At that time German subs were torpedoing coastal shipping, so smaller freighters used a channel between Miami and Key West, a protected waterway too shallow for undersea enemy subs to enter. During our work assignments I was able to slip overboard off the Florida Keys’ outer coral reefs and capture fish and lobster using a face mask and spear.

Our crew preferred the seafood to their more frequent wartime diet of canned Spam.” William next attended the Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut. There he served aboard a square-rigged cadet training vessel. “When we were underway,” William recalled, “we had to trim the sails. This required climbing up in the rigging to hoist and unfurl thick canvas that felt as if it were made of lead. From nearly one hundred feet above deck, the rolling and pitching of the vessel was magnified so that I felt as if I were on the end of a swinging pendulum.”

Following the end of the war, both William and his younger brothers became involved in the construction industry, erecting speculative homes in the exclusive Bal Harbour area of Miami Beach. Later, Stanley decided to enter the real estate business, while both William and Dudley began new careers in the documentary film business.

Capturing the Ocean In a Metal Box

“We decided to specialize in underwater photography,” William recalls of his earliest days in film. “This was before Jacques Cousteau, and no submersible camera housings were available, so Dudley and I had to start from scratch, setting out to design and construct our own. We purchased and taught ourselves to use a metal turning lathe from Sears Roebuck, along with other basic equipment. Fortunately, I had my two years of pre-engineering at the University of Michigan, along with my metal working experience in the aircraft factory. Our final product worked to perfection. We now had a compact, watertight housing that allowed full camera control from beneath the sea except for changing film. On April 7, 1948, the U.S. Patent Office issued us a patent on our design.”

Both William and Dudley participated in two marine sports in which the film industry took an interest. Waterskiing was one, and underwater spear fishing was the other, both of which were new sports at the time. With their recently completed watertight camera, they worked on Paramount’s films enabling them to learn cinematography above ground from professionals in the industry.

“Dudley excelled at lining up promising contracts,” William recalled. “Our first film in which we participated was a Paramount release on water skiing, titled ‘Riding the Waves.’ This was followed by another Paramount movie, ‘Five Fathoms of Fun,’ where we shot all the below-sea footage. Paramount Pictures thought enough of this latter film to submit it for an Academy Award.

The next film my brother and I shot twelve thousand feet of film on the Hawaiian Polynesian Islands prior to statehood. To capture on-location close-up surfing action, we constructed a very lightweight wooden tripod large enough to support two cinematographers and their equipment. Using a hollow surfboard permitted us to float our platform out onto the submerged coral reefs.”

Passage to Tahiti

Shortly after their work with Paramount Pictures, Louis Valier, an old school mate, invited William to join him and a native Tahitian aboard his thirty-two foot sailboat, “Teri”; their destination: Tahiti in French Oceania. William had always dreamed of visiting the South Seas and this presented too good an opportunity to pass up.

“I gathered my camera equipment together along with thousands of feet of film for our November 3rd, 1949 departure,” William remembered excitedly. “Our passage across the equator and beyond into the southern latitudes was time-consuming. We finally entered Tahiti’s Papeete’s Harbor in a tropical downpour on December 16th.

“A few days later I met a tall, slender Tahitian in her early twenties

named Leisa Doom. I found her intelligent and attractive, with long dark hair that fell almost to the ground. After a night of dancing she accompanied me to my thatched roof cottage and spent the night. The following morning I almost thought I was still in a dream. Surrounding the bed were a number of chairs occupied by my Tahitian girl’s Wahine friends. Leisa and I got along well and she proved a valuable companion.

“During my year in the South Seas I exposed fifteen thousand feet of sixteen millimeter Eastman color film. My plans were to reside in French Oceania about two months. Unfortunately, we arrived just as the rainy season commenced. It wasn’t until March that the rain tapered off and I was finally able to shoot the first foot of film.

veted status. The film ‘The Sea Around Us’ won an Academy Award for a documentary, of which Dudley and I filmed one-third of the underwater scenes for this highly publicized release.”

Upon his return from the South Seas in 1949, William became deeply involved with tropical fruit culture. Over the years he had been active in making new tropical fruit introductions. “I believe I have introduced more tropical and subtropical fruit and fruit varieties in the U.S. mainland than any other experimenter except Dr. David Fairchild,” William said. “The mainland areas that are able to grow some of these are California and Southern Florida.”

William’s visits to collect rare fruit included the West Indies, Asiatic Tropics and Central and South America. He continued to work in horticulture until the end of his life. He wrote and experimented extensively on the subject, including launching a worldwide organization called “The Rare Fruit Council.”

Marriage and Raising a Family

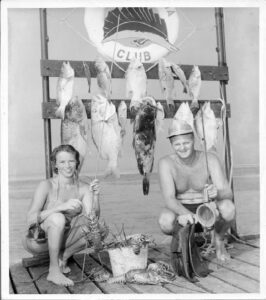

Following World War Two, William and Dudley spent a lot of time in

the Bahamas, waterskiing, spearfishing and shooting undersea footage for the film industry. One afternoon William met a Bahamian named Dorothea Carroll, who would soon become his wife. Dorothea was born on December 16, 1931, in Georgetown, Great Exuma, Bahamas. Her family goes back 300 years in the Bahamas, and this is where she met William water skiing, in Nassau, Bahamas. The two had many great years together surfing and spear fishing, both being natural water athletes and sharing the love of the ocean. Dorothea was petite at 5’2” and 98 pounds when they met but could out-spearfish the men

and free dive to over 60 feet. In the years that followed, they had four children; the first had a defective heart and did not survive. The other three were named Christopher, Pamela, and Eric.

Over the years, members of the Whitman family have surfed the West Indies, Europe, South and Central America, Hawaii, The South Seas and Australia. Chris Whitman won the Hawaiian Championships at only eight years old. Dudley’s daughter Renee took top honors at the first East Coast Surfing Championships held near Cape Kennedy. On January 10,

1998, both William and his brother Dudley were inducted into the East Coast Surfing Hall of Fame as surfing pioneers. For the Whitmans, their legacy of surfing for fun does not end here. Following in their father’s footsteps is the second generation of Whitmans, Chris, Pamela, and Eric, as well as an up and coming third generation. Chris was one of the first commercial longan grove operators in Miami, Eric worked for NASA at the Kennedy Space Center and Pamela became an airline Captain.

Editor’s Note: I first met La Jolla resident Pamela Whitman Mattson several years ago and we discussed producing some sort of editorial on her family. Thus, it has finally come to be. Before we conclude, a short autobiography about Pamela must be included, for it is obvious she definitely inherited the Whitman drive for success and adventure.

Pamela Whitman Mattson

I started surfing in Waikiki at the age of five in 1961. My father pushed me into a wave in front of the old Outrigger Canoe Club on the inside against my will and I panicked. That ended my surfing until our next visit to Hawaii in 1963, and at age seven I totally took to the sport. Literally, everyone in my family surfed. My father, mother, older brother Chris (by 16 months), younger brother Eric (by 7 years), Uncle Dudley, his four children Dudley Jr., Renee, Billy and Todd, as well as Uncle Stanley. It was a family affair and we took many surf safaris together. Some of the most notable were trips to Hawaii and Eleuthera, Bahamas. My father took our family all over the world surfing. As children we spent alternate summers surfing in Hawaii or Europe (Biarritz, France and Newquay, England). As teenagers we took many surfing safaris to Barbados, Puerto Rico, French Polynesia and Bali. The most memorable surf trip was in the summer of 1975, when our family traveled all through Southeast Asia. We took a train from Thailand to Malaysia, flew to

Singapore and on to Java. We visited one of the largest botanical gardens in the world in Bogar, Java, then took another train to the tip of Java and a boat to Bali and we surfed Kuta Beach. I didn’t even know where Bali was back then. It was unbelievably magical at that time, with few tourists and uncrowded waves. In Thailand, because of my father’s tropical fruit connections, the government met us and took us to remote jungle locations in the golden triangle where three countries meet (Thailand, Laos & Cambodia) searching for new rare tropical

fruit varieties. After spending three weeks in Bali we flew to Sydney, Australia, and then Tahiti. In French Polynesia we surfed at Huahine, then returned back to Miami, Florida. To this day that was the trip of my lifetime.

My father was such an adventurer and loved to travel and explore. If it was an off limits area my Dad would make sure he explored that! He had a very curious mind. After graduating from The University of Florida with a Bachelor’s Degree in Advertising, I moved to the North Shore of Oahu in 1979, and still reside there part time. I competed in the surf contests covered by The ABC Wide World of Sports at Sunset Beach, and The Women’s World Cup of Surfing in Haleiwa (1980, 1981 & 1982). Since I didn’t follow the circuit around the world, I had to pre-qualify each year by entering the Women’s Pro Class Trials. In 1982, I started flying helicopters on a whim and enjoyed it so much I became a flight instructor in the Hughes 300C, a small two seater piston engine chopper. The owner of the company who trained me, Steve Fern of Hawaii Pacific Helicopters, hired me for my first job as a Flight Instructor. I trained over ten students, many who earned their Commercial Rotorcraft ratings. I then transitioned to the jet helicopter Hughes 500D and flew tours out of Waikiki at a heliport located right in front of the Ala Moana Bowl surf spot. After flying helicopters commercially for three years, I got my airplane ratings, seeing an opportunity to perhaps apply to the airlines, which offered higher pay and benefits. I flew small Cessna 206 cargo planes inter-island to build up my hours and then finally got my first break flying for Mid Pacific Airlines in 1987. I flew a sixty passenger turbo prop plane called a YS-11 inter-island. I worked for that company for one year until they went out of business. Aloha Airlines expanded at that time and I got hired in February of 1988 to fly the 737 inter-island jets as a First Officer. In June of 1988, I made history piloting the 737, making the first all female crew with Captain Mimi Tompkins. I upgraded to Captain in two and a half years in 1991. I continued to fly for Aloha for 15 years until 2003, at which time I elected to take early retirement. Unfortunately, a few years later, Aloha went out of business after over sixty years in operation, leaving many employees devastated and unemployed. My career at the airlines was remarkable, exciting and very rewarding. I still fly from time to time for pleasure and my love of surfing has never diminished.

I would very much like to speak with Pamela Whitman Madison, or one of her siblings, about her father and his many trips in search of tropical fruits. I am the chairman of a fruit club in Sarasota, the Tropical Fruit Society of Sarasota. I am preparing a slide presentation about the Fruits of the Genus Artocarpus – breadfruit (one her dad’s favorites), jackfruit, and many others. I have a few slides about Mr. Whitman in my talk, as he was one of the founders of tropical fruit gardening in Florida. Very few people in this hobby are aware that had it not been for the fact that Bill Whitman spent a year in Tahiti, and came home with a love for breadfruit, there may not have been any tropical fruit clubs in Florida. Everyone who enjoys this hobby owes a debt to him, and I would like to learn a bit more about him and his interest in breadfruit, for inclusion into my presentation.

The foto of Bill Whitman on an early model surfboard

Sure looks like a female..?!?

Yes it kind of does. The article was written by a family member so we have to assume that they captioned it correctly.

I was friends with Chris Whitman. He was Bill Whitman’s son. I remember Chris and I drove to California around 1972. We ended up in Mexico camping. We split up in Mazatlon mexico. Chris hichhiked all the way to Costa Rica. Lived in the mountains with an Indian tribe. Took pictures. He didn’t come back for maybe a year. He was 17 or 18 years old. He was an interesting person. Not afraid of doing new stuff. The whole family was like that. I should call him. It’s been 45 years since we spoke.

Ken V

The Whitman family were pioneers of Florida surfing. We hope to post more on the Whitman’s influence soon…