The Long, Strange Tale of Ron DiMenna

by Matt Higgins, ESPN

Ron Jon’s Cocoa Beach flagship, the anchor of a nine-store retail surf empire. (Courtesy Ron Jon Surf Shops)

The legend says he’s as camera-shy as Bigfoot, or Banksy. A rap sheet tells of a taste for fast living. The rumors? Oh, boy, where to begin Let’s start with a story about a surf mogul who hates publicity.

It was 1988, and Ron DiMenna, founder and owner of Ron Jon Surf Shop — “The World’s Most Famous Surf Shop” — was embroiled in a zoning dispute with city leaders in Ship Bottom, N.J. The beef concerned an outdoor display at his original surf shop. A judge threatened to shutter the business and throw DiMenna in jail for failing to pay mounting fines. Several newspapers covered the story, including The New York Times. The store’s manager provided quotes. DiMenna, however, was unavailable for comment because he was riding horses in Tasmania; at least that’s what a tall man named Joey, who claimed to be his assistant, said.

“What’s your last name, Joey?” a reporter asked.

Thinking fast, DiMenna blurted, “Norton. I’m Joey Norton.” Norton being N-O-T R-O-N spelled backward, DiMenna has adopted the nom de guerre permanently.

Today, DiMenna, a.k.a. Ron Jon, a.k.a. Joey Norton, at 74 years old continues to flummox journalists. He has hardly had his photograph taken in four decades — mug shots notwithstanding (more on that later). He runs a nine-store, $30 million-a-year retail empire stretching from Canada to Key West from a wandering luxury motorhome that he bought for $500,000 and customized with a paint job that makes it look like an old woodie. If he behaves as if pursued by something, perhaps it is his reputation.

“Only some of the stories are true,” he said, speaking on the phone from his motorhome, parked for the time in a barn in an orange grove on 175 fenced acres he owns on an island near Cocoa Beach, Fla. — site of the flagship Ron Jon Surf Shop. He’s got some cattle out back. His wife, Lynne, and their two Australian Blue Heelers are there, too. It’s his home, what he dubbed The Rubber Ranch — prison slang for the psychiatric ward.

“Only some of the stories are true,” he said, speaking on the phone from his motorhome, parked for the time in a barn in an orange grove on 175 fenced acres he owns on an island near Cocoa Beach, Fla. — site of the flagship Ron Jon Surf Shop. He’s got some cattle out back. His wife, Lynne, and their two Australian Blue Heelers are there, too. It’s his home, what he dubbed The Rubber Ranch — prison slang for the psychiatric ward.

Speaking of stories, 50 years after opening his first surf shop in New Jersey, DiMenna dreams of a new project: He wants to sum up the sweeping historical narrative of surfing in something he calls The Experience. Blueprints call for an 80,000-square-foot museum in Cocoa Beach that will unify board sports — skateboarding, snowboarding, windsurfing, etc. — and all the brands together under one roof, with exhibits “telling the story,” he says, of how surfing spawned it all. There are a slew of surfing museums already — four at least in California alone, but none as ambitious as what DiMenna has designed.

The structure would be adjacent to Ron Jon’s flagship store — the aqua- and sand-colored colossus at the corner of State Road 520 and A1A surrounded by skateboarding, surfing and Polynesian statuary that looks like it was plucked from the Vegas Strip and plunked down a few blocks from the ocean. Open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, for the convenience of the 1.5 million souls who come here each year (more than visit the nearby Kennedy Space Center) the store contains 52,000 square feet of bikinis, board shorts, beer cozies, sunglasses, shot glasses, key chains and especially T-shirts.

Surfboards? They’re on the second floor. “We feel it’s important to stay true to our brand and our heritage,” said Heather Lewis, a spokeswoman, noting that “the bulk of our sales come from other items.”

Over the years, Ron Jon’s has sold shark’s teeth necklaces, boomerangs, stuffed koalas, iron crosses, waterbeds and waterpipes (bongs) earning it the nicknames Rob Jobs and The Supermarket Surf Shop. DiMenna sold so much stuff that purists accused him of selling out.

Others, however, point out that Ron Jon played a pioneering role in helping transform surfing from a cottage industry into a multibillion-dollar business. Before industry leaders Quiksilver and Billabong opened stores in Times Square, and Volcom and its “Youth Against Establishment” slogan sold for $608 million to the French luxury retail conglomerate that owns Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent, folks from Texas to Toledo, Ohio, bought Florida surf shop T-shirts, and placed free stickers (Ron Jon’s gives away 2 million annually) in the window of their pickup trucks.

“What you see today stems from his open-minded merchandising, which got surfing out of its cool doldrums into the general population,” said Duke Boyd, who basically invented surfwear in 1962 when he co-founded Hang Ten. “He saw very early on the broad vision of surfing, versus the minor one.”

For this and other contributions, DiMenna was inducted into the East Coast Surfing Hall of Fame in 1998. In 2009, Boyd attempted to include DiMenna in his book, “Legends of Surfing,” a series of profiles of the most significant figures in the history of the sport, from Duke Kahanamoku to Kelly Slater. There was only one problem: DiMenna refused to provide a photograph.

“He’s a little quirky in the sense that he doesn’t want his picture taken,” Boyd said.

DiMenna generally doesn’t talk to reporters, either. “He’s a private person,” a Ron Jon spokeswoman said. “He doesn’t do interviews.”

In Cocoa Beach, I found the doors of his store flung open wide for the world to enter. But Ron Jon the man remained inaccessible, protected by fences, functionaries and a thick cloud of secrecy.

Former employees dodged my phone calls. Those folks around town who had some dealings with DiMenna either declined to talk or told potentially libelous tales that could not be confirmed, and then requested anonymity. “Too many skeletons,” one woman explained.

Surfers like Jeff Hakman were both infamous and legendary for their exploits, which helped build the surf industry. (Merkel/A-Frame)

My raw materials amounted to little more than rumor and a police record, so I attempted to buttonhole DiMenna, driving to a Brevard County, Fla., courthouse where at 8:56 on a hazy May morning I witnessed the space shuttle Endeavor boom into the sky above Cape Canaveral, tracing a trail of fire and smoke before vanishing into the clouds. DiMenna was scheduled to appear, regarding a December charge of driving under the influence (his third in Brevard County). He didn’t show. His lawyer said he wouldn’t be coming.

I dug up DiMenna’s unlisted number and left a message. Next I called New Jersey and the 81-year-old Reverend Earl Comfort, who on a fateful day in 1959 invited his neighbor in Manahawkin, N.J., for a surf. The neighbor, a former Marine working at his father’s grocery, was DiMenna. Hooked, DiMenna soon bought three boards from California. A few transactions later, by 1961, in what has become part of the lore in the Ron Jon Surf Shop company literature, he opened a shop on Long Beach Island, a seaside playground for folks from Philadelphia and New York, with a powerful shore break.

Immediately Long Beach Island’s city fathers were skeptical of surfing and Ron Jon’s, and especially dubious of Ron. “They thought we were all drug runners,” Comfort said. “The image that we were a bunch of hippies was a fable.”

“In the early days, you needed to get in his shop. We got into Ron Jon’s shop and we exploded because of him.”

— Duke Boyd, co-founder of Hang Ten surf clothing

In the cultural ferment of the 1960s, scrutiny of surfing operations was not unusual. By the 1970s, Mike Hynson, co-star of the iconic 1966 surf documentary “The Endless Summer” — which introduced the world to the wanderlust that makes surfing, in part, so romantic — was stuffing hollowed-out surfboards with drugs for shipment back to the States as an associate of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, a new-age cult and drug ring that had adopted Timothy Leary.

Jeff Hakman, one of the top competitive surfers of the era, had discovered smuggling and heroin, too, about the time he was founding Quiksilver USA, which after a few transactions would go on to become the biggest surf apparel brand in the world.

Pondering these associations — and following a week of mostly fruitless phone calls and trips around town in a rented Dodge Challenger with a powerful Hemi engine — I wearily hopped a plane bound for home, despairing that I would ever reach DiMenna.

That’s when he called back.

He was gruff initially. What was I up to? He demanded to know my motives for discussing his criminal history. He suggested parameters for my story, conditions he had imposed on others, including an Australian national TV program that profiled him twice without ever showing his face. He said:

“You’re going to beat me up.”

“You’re going to piss off a lot of people. Is that what you want?”

He said something about his business, adding: “If you print that, I’ll kill you. I know people in New York. Trust me.” Then he laughed. DiMenna laughs a lot.

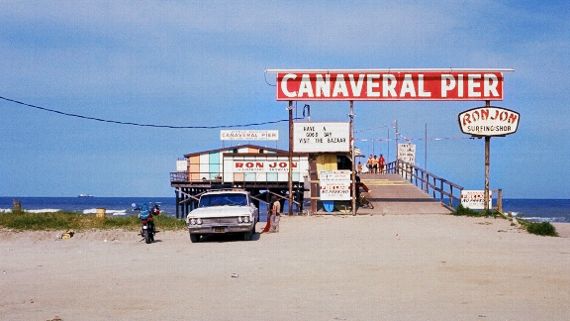

Ron Jon’s in the ’60s, long before the T-shirts, boomerangs or legal troubles. (Courtesy Ron Jon Surf Shops)

He talks a lot, too, once he gets going. He told how in 1963, wanderlust led him to place his father in charge of the New Jersey store while he set out in a camper, fetching up at Cocoa Beach, a place with sand the color of a faded catcher’s mitt that snared swell from several directions. He set up a small shop and with sensibilities shaped at his father’s supermarket, DiMenna worked hard selling the incipient surfing lifestyle.

“If you could get in his shop, you could be successful,” Boyd said. “In the early days, you needed to get in his shop. He was a major influence for Hang Ten. We got into Ron Jon’s shop and we exploded because of him.”

Speaking of explosions, as his business grew, DiMenna explored new hobbies.

By the 1970s he had developed a dynamite fetish. He would send trees somersaulting 150 feet in the air from New Jersey’s pine barrens, once nearly impaling a low-flying plane. He smuggled sticks on a surf trip to the Bahamas in dog food containers and blasted a 100-foot geyser from a gin-clear cove, diving in and spearing hundreds of pounds of stunned fish.”It was very safe,” he said. “We had fun.”

Federal authorities, though, noting suspicious signatures on orders of dynamite, believed DiMenna was supplying a Philadelphia motorcycle gang with explosives for use against rivals. A judge gave him four years’ probation.

“Can you imagine if I was playing with dynamite today,” he said with a laugh. “They would stick me away forever.”

They’ve tried.

Narcs floated around the fringe of his store. The pay phone out front was bugged. DiMenna says he was selling a lot of merchandise, but not drugs.

Then, in 1975 he was caught on a wiretap attempting to acquire what he says was methamphetamine. He says he used the stuff to fuel long hours at work converting old boat hatch covers into furniture, a big seller at his New Jersey shop.

He spent almost 18 months in New Jersey state prisons, running his shops using carbon-copied, handwritten letters, and spending hours on the phone with his managers, trading cigarettes to other inmates for their telephone privileges.

How horrible was prison?

“I had fun in there, too,” he said. “I make the best of things wherever I am.”

Authorities believed DiMenna was steeped in drug trafficking. Later, he says they admitted, “Ron Jon, you’re not who we thought you were.” In 1994, New Jersey Gov. Jim Florio pardoned DiMenna for his drug conviction.

Still, Cocoa Beach and Ship Bottom are small towns. A reclusive surfing millionaire with a criminal history tends to get people talking. For kicks DiMenna sometimes tells his board of directors the rumors he’s heard, like the one about the yacht moored prominently in the Banana River off Cape Canaveral that was supposedly used by Ron Jon as a drop station for drug shipments.

Noting the endurance of such myths, his wife sent a letter requesting “Ron’s positive story for a change.”

By then DiMenna had become my Moby Dick, and as with the relentless and crazed Captain Ahab, the chase raised discomfiting questions about character (chiefly mine). I could see how from a certain perspective my assignment resembled little more than harassment of an icon attempting to live out his golden years in relative peace.

“He’s a nice guy,” Dick Catri, a contest organizer considered the Godfather of East Coast surfing, said about DiMenna. Catri once ran a rival surf shop in Cocoa Beach and recalls DiMenna lending money to competitors in need.

“Ron is a very brilliant businessman,” Catri said. “Ron has had extremely good management in the store from the beginning.”

It was good management that allowed DiMenna to light out on the road at any time while his workers minded the store. DiMenna reckons he’s spent 16 of the past 20 years traveling.

Once, he shipped his ride to Australia, stayed for seven years and gained citizenship, sending surfboards, stuffed koalas and boomerangs back to his stores in the States. “When I got there, the first thing I wanted to see was the water go backwards in the toilet and in the sink, and throw a boomerang,” he said. “I thought, well, if I got this desire then every male, or at least 50 percent of them, would want to try one. So I started shipping boomerangs. We sold 20,000 of them in less than a year.”

For his next move, though, DiMenna has mulled selling Ron Jon’s. He might have to in order to pay for The Experience, which he reckons will cost around $60 million. And with Volcom selling for $600 million, he would be foolish not to at least look into what his brand is worth.

Meanwhile, he’s sponsored a design for a signature “Endless Summer” surfing license plate for Florida. The license plate and The Experience fall under the direction of Surfing’s Evolution & Preservation Foundation, Inc., a nonprofit set up by Ron and his wife which will plow proceeds back into the beaches, for cleanup, lifeguards and ecology.

Speaking of licenses, in May a judge revoked DiMenna’s driver’s license for five years after he pleaded no contest to charges of driving under the influence. During a traffic stop in December police discovered in his truck a container of Four Loko, a malt liquor known to hard-partying college students as “blackout in a can.”

Not to condone that sort of thing, but the episode may be little more than a bump in the road. DiMenna already has a design for a double-decker motorhome with a separate entrance and living quarters for a personal driver. On the upper tier, he envisions a suite with a commanding view of waves of asphalt leading to new adventures beyond the next bend in the road.

Out there life comes at you at high speed, its ineffable questions hovering along the highway like Ron Jon billboards. I have spent enough time traveling lately to formulate a few questions myself, about whether a man can be measured by his misdeeds, or even the size of the monuments he’s constructed. I have thought on these matters, and on DiMenna’s “only some of the stories are true,” and still something else he said several times: “I am who I am. I like who I am. And I’m going to be who I am.”

It might not all fit neatly on a museum display. But you get the picture.

Republished from the original article by Matt Higgins:

http://espn.go.com/action/surfing/story/_/id/6966333/ron-dimenna-ron-jon-story

Pretty cool story well done…..!!!